OptimalFilterPhonon¶

Note: This page contains large chunks of text stolen verbatim from Jeff Filippini's writeup for R123/4. He should be given proper credit for being the author.

Overview¶

This routine is the simplest optimal filter routine in cdmsbats. It is used for reconstructing phonon pulses. Each phonon trace is fit independently with filters generated from the FFT of the pulse template and the noise PSD. The delay (i.e. start time relative to trigger) is determined by fitting over a range of different times which differ by 1 digitization bin (typically 0.8\mu s). The fit that returns the largest amplitude is the one that is assigned the delay.

The OptimalFilterPhonon routine was ported from Darkpipe and is identical to the implementations used in Darkpipe for the R123/4 and prior analyses. It was originally named OptimalFilterPulse, because it could also be applied to charge traces. Since it has always been applied solely to phonon traces, later it was renamed to OptimalFilterPhonon in an attempt to resolve ambiguity.

One pulse template is used for all phonon channels at all energies and all events. ZIP phonon pulses exhibited a strong position and energy dependence. Hence the optimal filter fit result was systematically biased based on the energy and position. This systematic bias was removed through application of the position correction as a post-fitter process.

For iZIP reconstruction (R133 at Soudan and onwards), we will implement a “non-stationary noise” version of the optimal filter, which will not suffer from as much position-dependent bias. The non-stationary fitter will serve as the primary energy estimation for iZIP detectors. However we retain the use of the OptimalFilterPhonon for the study of position-dependence and as a cross-check for other energy estimation algorithms.

Theory¶

Given a noisy signal, optimal filtering attempts to estimate the signal amplitude in a way maximally robust to measurement noise. It can be shown that optimal filtering gives the optimal resolution possible in the case of a known pulse shape and a known spectrum of Gaussian noise. Keep these assumptions in mind when thinking about optimal filtering, as the result can be degraded by variations in pulse shape or noise characteristics.

Motivation¶

Suppose we want to estimate the height of a pulse of known shape in the presence of noise (assuming for now that the start time of the pulse is known). In practice, we want to best estimate the ratio of amplitudes between a template and a real (but noisy) pulse trace. One option is to just divide the peak height of the trace by the peak height of the template. This is clearly susceptible to noise, however - a noise fluctuation in the measurement in a single digitizer bin can change the peak height, leading to substantial errors for small pulses.

Time domain fitting¶

To be more robust to noise, we'd like to take the entire pulse trace into account. We can do this by performing a one-parameter fit in the time domain, finding a multiplication factor for the template pulse which minimizes the \chi^{2} between the multiplied template and the real trace. This provides good performance, is easy to compute (the fit is linear), and is provably optimal in the case of white Gaussian noise (i.e. noise with a flat power spectrum). This method can also optimally account for situations in which the noise power (i.e. the variance of the noise) varies with time in a known way, but we normally assume the noise is stationary and ignore this subtlety.

Time-domain fitting has significant drawbacks in the case of non-white (though stationary) noise, however. Non-white noise introduces correlations in the noise at different times, and so the various digitizer bin measurements are no longer independent and a time-domain \chi^{2} minimization is no longer equivalent to a likelihood maximization.

Frequency domain fitting¶

The solution is to perform the same one-parameter fit in the frequency domain using the Fourier transforms of the trace, template and noise. The different frequency components of Gaussian noise are uncorrelated, so a frequency-domain \chi^{2} minimization is perfectly fine. We can account for the variation in noise with frequency by treating the noise spectrum as a set of error bars for the corresponding frequencies of the trace's Fourier transform. This is exactly what optimal filtering is - a one-parameter fit in the frequency domain, accounting for the dependence of noise variance with frequency. The resulting estimate naturally weights each frequency component based on its signal-to-noise ratio at that frequency, efficiently excluding even very large noise peaks. In the case of white noise it is equivalent to time-domain fitting, it just wastes a little time on FFTs.

Method¶

The optimal filtering algorithm assumes that we can express the observed signal in the form S(t) = a \cdot A(t) + n(t). If we express each of these as a series of Fourier components (indicated with subscripts), the optimal estimate of the amplitude given a known start time t_{0} is:

\hat{a} = \frac{\sum{\frac{A_n^* S_n e^{i \omega_n t_0}}{\sigma_n^2}}}{\sum{\frac{|A_n|^2}{\sigma_n^2}}}

with estimate variance

\sigma^2_{\hat{a}} = \left(\sum{\frac{|A_n|^2}{\sigma_n^2}}\right)^{-1}

This methodology can be used to compute the resolution in start time and amplitude attainable with this method using second derivatives of the \chi^{2} expression. These should be relatively accurate for the charge signals, though pulse shape variation will have substantial systematic effect on the phonon estimates.

Fitting for the pulse start time¶

Since triggers may occur at slightly different points along a pulse, we commonly need to fit for the pulse's start time in addition to its amplitude. This can be done relatively simply by computing the optimal filter amplitude for each of a series of time-shifted templates, each moved to the left or right in the digitizer window by some number of bins. The best estimate of the true time shift is given by finding the time shift which maximizes the computed amplitude. This seems to greatly increase the number of optimal filter operations which must be performed, but the actual performance hit is not terrible because the time shift can be performed after Fourier-transforming the pulse (no additional FFTs are needed).

Practice in CDMS¶

Noise¶

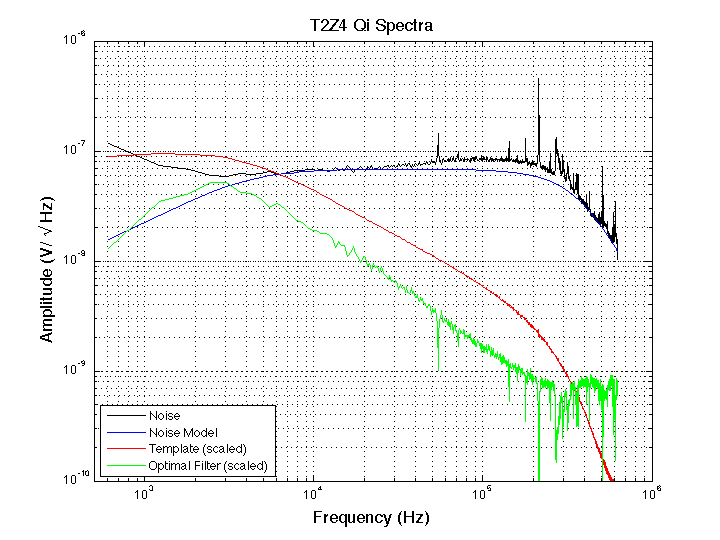

At the outset of each data run, 500 digitizer traces are taken on all detectors with random triggering. The traces constitute a sampling of the noise on each channel during the run. After a cut to exclude traces with large fluctuations (which may contain pulses), the remaining set of true noise traces is Fourier transformed and averaged to produce an estimate of the power spectral density of the noise. This estimate is computed only once for a given data set, then stored in noise files for use on later event files.

Note that this method implicitly assumes that the noise is stationary on time scales longer than the Nyquist frequency of the digitization window. If the noise spectrum varies substantially with time (e.g. due to cryocooler cycles), the resulting spectrum will overestimate the noise for some events and underestimate the noise for others.

Templates¶

Phonon templates are generated using estimated rise and fall times and a simple two-exponential form (pulse.m) for each detector. The templates are typically generated at the beginning of a data-taking period corresponding to a refrigerator run. Before processing each series, the FFT of the template is taken and then stored in the filter files for use during the BatRoot stage of the data processing.

The rise and fall times are estimated from data, but are not very useful due to large variations with pulse energy and event position. This contributes to substantial variations of measured energy with event position and energy which must later be corrected with the position-correction process.

Possible Extensions/Improvements¶

Additional fit parameters¶

The optimal filter algorithm can be extended to fit for more parameters in the frequency domain, possibly even for the entire pulse. Such fits are nonlinear and so naturally slower than optimal filtering, but should in principle not be significantly slower than equivalent time-domain fitting procedures (the cost is basically that of performing a single FFT). A frequency-domain fitting algorithm should be robust to both noise and pulse shape variations and possibly lead to improved resolution in timing parameters and new avenues for discrimination. The practical difficulty appears to be that the Fourier transform of a smooth time-domain function can show substantial oscillation in the frequency domain, making fits more complex. Without a full understanding of our phonon pulse shapes, it is also difficult to choose a sufficiently accurate functional form.

Varying phonon templates¶

Obtaining good performance with this method depends on the use of a good functional form of the pulse. One possibility is to choose the optimal filter template separately for each phonon pulse based on a time domain fit. This is a promising idea, but initial work (see note by Brooks in References list below) suggests that it does not provide a large benefit in amplitude resolution.