Throughput Time Series Patterns (Diurnal and Step Functions)

Les Cottrell, Connie Logg

IEPM-BW time series |

Diurnal fits for:

BBCP disk,

BBCP memory,

BBFTP,

Iperf

|

Throughput Time Series Patterns (Diurnal and Step Functions)

Les Cottrell, Connie Logg |

|

| |

The achievable iperf TCP throughputs seen in Fig. 1 vary by more than a factor of 10 from site to site.

Figure 1: Logical routes to the remote IEPM-BW sites

(October 2002). shows the

logical routes from SLAC. The boxes with bold outlines are monitoring sites in

their own right. The labels in italics in boxes indicate the host has a

100Mbit/s connection. Other hosts have Gbits/s connections. The box shading

indicates the participant type. Diagonal lines are for PPDG/GriPhyN/HENP

collaborators, hashed shading indicates the site is a network measurement

collaborator, and the un-shaded boxes are for European Data Grid collaborators.

The clouds are for Internet Service providers (ISPs). The grey lettering in the

clouds indicates the "GigaPoP" (e.g. ATL means Atlanta). The numbers by the

sites indicate the average measured throughput from August 24 through October

26, 2002. For the measurements reported SLAC had OC12 (622Mbps) connections to

ESnet and Internet2.

By design, hosts with 1000GE NICs had higher speed connections

(typically 622Mbits/s) to the Internet and, as expected, higher performance is

observed. By using large windows and multiple streams we were able to measure

throughputs of several hundreds of Mbits/s across both transcontinental and

transoceanic links.

Viewing our time series plots of the throughputs, we observe two

major types of behavior that may overlap at times. 1.

Sudden step changes in throughput. These are usually associated with a

network change, e.g. a new route, or a link upgrade. They may also be associated

with a remote host change, e.g. a new CPU or a change in the Network Interface

Card (NIC) used.

Figure 2: Time series of iperf TCP and other throughputs measured from SLAC to

CERN for 28 days starting Nov 2, 2002. Also shown are the ping minimum as grey

bars and average Round Trip Times (RTT) as red bars. 2.

Oscillations in the throughput on a daily basis, e.g. high throughput at

night or weekends when there is lower utilization and congestion, and higher

performance at other periods. We refer to the daily changes as diurnal

variations.

Figure 3: Time series of iperf and other throughputs from SLAC to Caltech for 28

days starting Nov 2, 2002. If the time series are fairly flat (e.g. there are only small

diurnal changes) then sudden changes in throughput show up as multimodal peaks

in histograms of the throughput (see Fig. 4). They also show up in the moving

averages with large relative standard deviations for the set of points close to

the change. Fig 4: Histogram of the iperf TCP throughputs for

Fig. 3. The red line shows the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF). About 25% of the remote hosts exhibit large diurnal variations..

For such hosts we use a simple fit to: f(x) = abs(a) * sin(x + b) + c where x = time of day (in

radians, i.e. start of day = 0, end of day = 2 * pi). We use as the

least-squares fit starting values, c = average throughput, a =

standard deviation of throughput, and c = pi/2. This fit enables

an easy characterization of the diurnal variability. The fitting can be further

simplified, by noting that b (the phase angle) should stay fairly

constant for a given site (if there is a diurnal variation then the

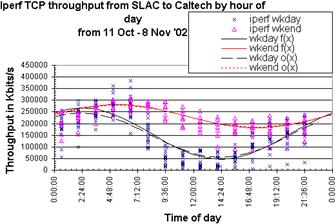

busy/congested periods are likely to be the same from weekday to weekday). Fig 5

shows a least-squares fit to iperf TCP data measured from SLAC to Caltech from

October 11 to November 8, 2002, where the x axis is the time of day of the

measurement, and the weekday measurements have been separated from the weekend

measurements. Also shown are the curves (dashed lines) from simply using the

starting values for a and c, and leaving b at the value

found in the fit. It can be seen that we can do almost as good with the simple

fit, and not have to resort to least-square fitting techniques. The difference

in the fitted value and initial estimate can be expressed as diff = abs((fit-initial)/fit)

and yields median values (for 39 remote hosts) of < 2% for a and 6% for

b. Since a and c are simple to estimate from the data, and b

should stay roughly constant for a given site, this proves to be a simple method

for quantifying the diurnal nature of the data. We have found that we can roughly quantify the "diurnalness" of

the data for a given node by looking at the error on the fit parameter b

(db). In essence,

db determines how the diurnal nature

of the data is clearly defined to allow b to be well determined. Values

of db of < 0.2 appear to indicate

candidates for paths with large diurnal variations. We identify these large

diurnal variations by eyeball by looking at a plot such as shown in Fig. 5. For

Fig. 5 the values of db are 0.04

(weekday) and 0.1 (weekend). Current examples can be found in

Master Diurnal fit for iperf.sum. As expected, there is usually different and less diurnal

variation for weekend data. We are looking at ways to fold the diurnal

variations into the predictions, for example by predicting the value at some

time, from the value at the same time a week ago. Though this may be less

accurate than a prediction from more recent data, it may be of value if there is

no recent data.

Figure 5: Iperf TCP diurnal

variations. Weekdays in blue, weekends in magenta. The fits are to sin

functions.