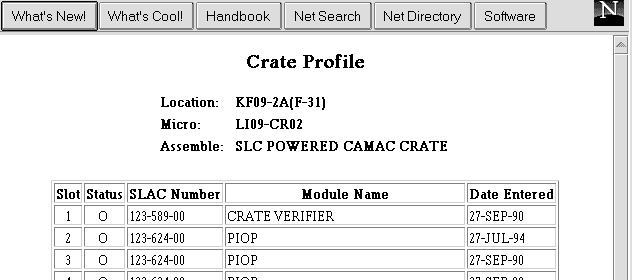

Figure 3 -- WWW screens of PEP-II Components List , and menu choices for each formal device identified by 'Primary, Micro, Unit'

A. Chan, G. Crane, I. MacGregor and S. Meyer

Stanford Linear Accelerator Center*, Stanford, CA 94309 U.S.A.

* Work Supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC03-76SF00515.

Abstract

A data warehouse grew out of the needs for a view of accelerator information from a lab-wide or project-wide standpoint (often needing off-site data access for the multi-lab PEP-II collaborators). A World Wide Web interface is used to link legacy database systems of the various labs and departments related to the PEP-II Accelerator. In this paper, we describe how links are made via the ‘Formal Device Name’ field(s) in the disparate databases. We also describe the functionality of a data warehouse in an accelerator environment. One can pick devices from the PEP-II Component List and find the actual components filling the functional slots, any calibration measurements, fabrication history, associated cables and modules, and operational maintenance records for the components. Information on inventory, drawings, publications, and purchasing history are also part of the PEP-II Database [1]. A strategy of relying on a small team, and of linking existing databases rather than rebuilding systems is outlined.

1. DATA WAREHOUSE—DO WE NEED IT?

In an accelerator laboratory we are inundated with data related to the fabrication and maintenance of the machine, such as hardware, personnel, finance [2]—yet it is more often than not quite difficult to obtain such related information in a useful format. To resolve a maintenance problem, one may need to log onto diverse computer systems and run different database software, frequently devoting much time to trying out obscure search strings.

Such compartmentalization of databases of the various accelerator departments evolved because different software was used to suit particular problems and situations. Although there is growing recognition to achieve database implementation under the same database software, we will still be faced to some degree with these differences. [3]

|

EPS File (18k) Figure 1 -- Types of implementation of data warehouse |

Another reason for this compartmentalization is that databases developed by the departments, of necessity, focus on their area of business functions. This short-term focus can be mitigated by recognizing the need to make linkages to the overall accelerator during the design of the database. However, the implementation of a data warehouse is required for a lab-wide view of decision support information for the accelerator.

2. DATA WAREHOUSE—FOR AN ACCELERATOR ENVIRONMENT

A data warehouse can be simply defined as [4] "a single, complete, and consistent store of data obtained from a variety of sources and made available to end users in a way they can understand and use in a business context."

There are 3 main architectures for a data warehouse (see Fig. 1), although in reality what is implemented is most likely a mixture of these different types. The data layers that Fig. 1 refers to are conceptual, rather than physical.

For the single-layer architecture, its strength is that data is only stored once, which avoids the need to synchronize multiple copies of data. Its weakness is that contention can occur between the online transaction processing systems and the decision support systems.

|

EPS File (18k) Figure 2 -- Linked SLAC accelerator databases |

For the two-layer architecture, its strengths lie in solving the contention between the online transaction processing systems and the decision support systems. It addresses the fact that end-user needs for information are different from what is easily available from real-time data. However, there is a high level of data duplication in the two-layer approach (with a tendency to become 'spaghetti code').

For the three-layer architecture, its strengths lie in the reconciled layer which is based on enterprise data modeling (i.e., a normalized database). This reconciled layer can support new, unanticipated end-user needs. The derived layer can be used to fill most end user needs, being the equivalent of predefined queries. The enterprise data modeling is a much more committed effort, and needs to be done incrementally.

At SLAC, we have mostly implemented the single layer and two-layer approaches.

The World Wide Web (WWW) technology has made it possible to access and link disparate databases, allowing the data warehouse to be a reality for us, and at a fraction of the programming effort in today's resource-scarce environment.

3. LINKING THE LAB DATABASES

Figure 2 is an overview of the lab's major accelerator-related databases that we have linked for the accelerator data warehouse. These systems are:

Table 1. Linkage of data elements.

| PEP-II Component List |

|

||||||

| Problem Tracking for Accelerator (CATER) |

|

||||||

| Cable Plant (CAPTAR) |

System Function QUAD:PR02,6072

|

||||||

| Equipment Tracking for Controls (DEPOT) |

|

Via WWW Common Gateway Interface (CGI) scripts, these databases

are linked together using common data elements (i.e., variations

of formal device

names shown in Table 1). The WWW interface gives excellent 'drill-down'

capabilities. Since linkages of the different databases are done

by the CGI scripts, huge savings in programming time are realized

as we do not have to create physical tables to join the databases.

Figure 3 -- WWW screens of PEP-II Components List , and menu choices for each formal device identified by 'Primary, Micro, Unit' |

Users can query the PEP-II Component List on WWW, and the search results will contain hypertext references that request information from the other database systems. In Fig. 3, among the search results returned for components in Region 1 Cell 12 is the Primary/Micro/Unit QUAD PR02 6072 (the three fields comprising the formal device name), which has a hypertext link that produces a menu with additional hypertext links to:

Figure 4 -- Summary and detail WWW screens of accelerator problem report database (CATER) linked from 'Area HER, Micro PR02' in figure 3 |

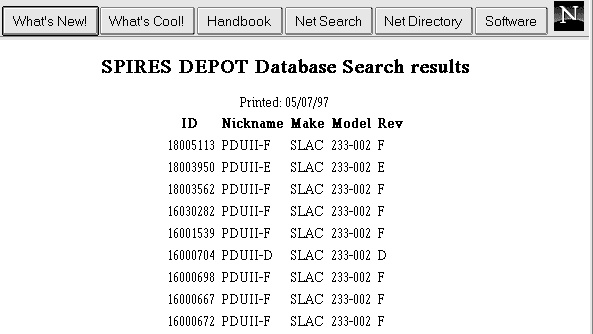

Figure 5 -- WWW screen of crate LI09/CR02 -- crate profile from cable plant database (CAPTAR), and linked history of modules in the Equipement Tracking for Controls database (DEPOT) which leads to maintenance history screens |

4. LESSONS AND ISSUES

This accelerator-wide view of the information delivered through the WWW interface has been popular with users, enabling more efficient work.

There are a few key issues that have enabled us to get to this stage for an accelerator data warehouse

With the ability now to link databases via a few common data fields, the integrity of the data stored in these fields need to be enhanced by cleansing the data and/or applying better database constraints. But this effort becomes easier when the benefits are now apparent to the users (even if it may not benefit their own department immediately).

In the future, we would like to rely more on commercial WWW-database tools (such as Oracle Designer2000, etc.), and less on CGI scripts which are time consuming and less secure.

The URL for the PEP-II Project Database is:

http://www.slac.stanford.edu/accel/pepii/db.htm

5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the continued support of the PEP-II management. We thank the people in PEP-II and the various Technical Division departments who manage the different databases, and who helped us analyze the linkages of these different systems. We also thank the student programmers who contributed to the WWW interface. We have drawn many lessons from discussions with members of the International Accelerator Database Group (IADBG).

REFERENCES

[1] A. Chan, G. Crane, I. MacGregor, S. Meyer, “The

PEP-II/BABAR Project-Wide Database Using World Wide Web

and Oracle*CASE”, Proceedings of 1995 International Accelerator

Database Group Workshop, Argonne National Lab, November 6-8, 1995.

[2] J. Poole, “Databases for Accelerator Control–An Operations Viewpoint”, Proceedings of 1995 Particle Accelerator Conference, Dallas, May 1–5, 1995, p. 2157.

[3] J. Poole, “Summary and Conclusions of the IADBG Workshop on Databases for Accelerators”, Proceedings of 1995 International Accelerator Database Group Workshop, Argonne National Lab, November 6-8, 1995.

[4] Barry Devlin, “Data Warehouse: from Architecture to Implementation”, Addison-Wesley, 1997.